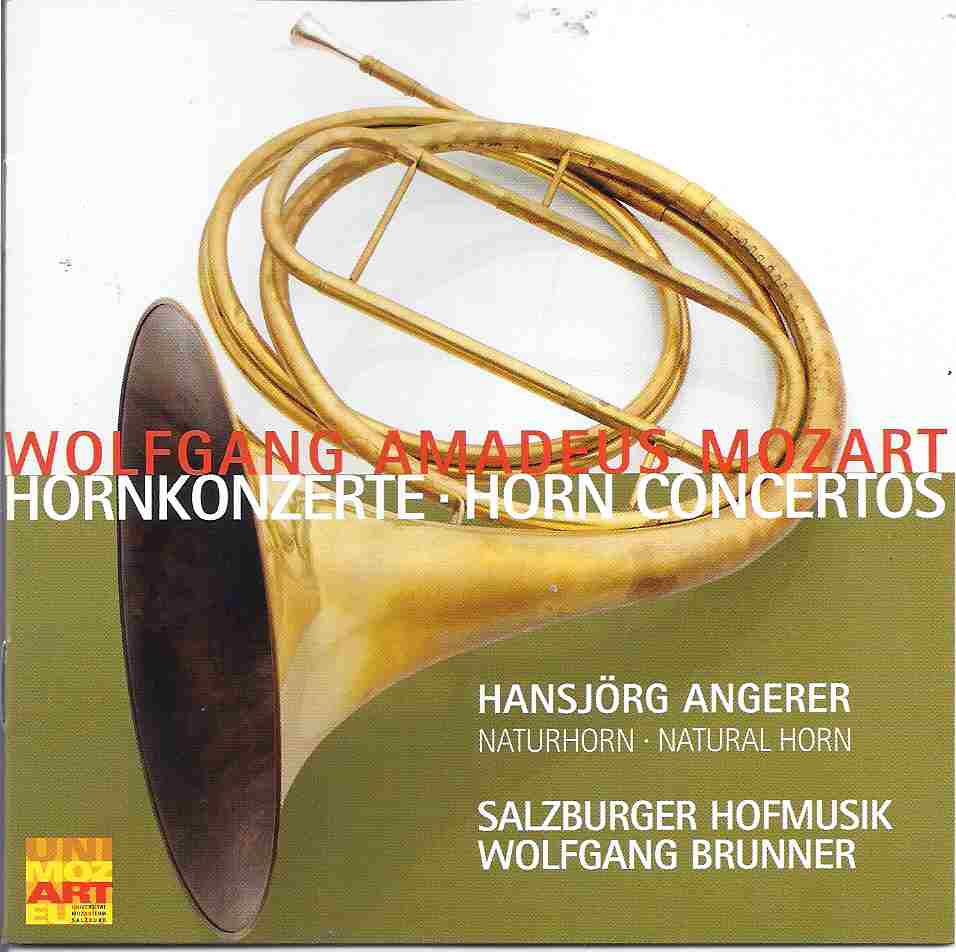

Recordings by Hansjorg Angerer’s Mozarteum Parforce

Hansjörg Angerer and the Mozarteum Parforce Horns, Jagdmusik am Kaiserhof zu Wien auf historischen Parforcehörnern, UNIMOZ 55, and Jagd Capriccio: Werke von Paul Angerer für historische Paforcehörner, UNIMOZ 56, Universität Mozarteum.

The Mozarteum Parforce Horns, led by Hansjörg Angerer, have recently released two fine recordings. The first, a collection of Hunting Music from the Viennese Court of the late nineteenth century, is an impressive compendium of music that will be of interest to any hunting horn enthusiast or scholar interested in the history of horn playing in Vienna. The second recording, a collection of contemporary music written for the historical instrument, is on par with other recent recordings of modern compositions for natural horn, such as Jeffrey Snedeker’s fine CD, The Contemporary Natural Horn, from 2010.

The first set of CDs I listened to was the collection of historical pieces. The music and playing presented on this collection are both wonderful and numerous mental images abounded as I enjoyed listening to the music: hunting choruses, huntsmen on horseback, hounds barking and chasing prey, lively pastoral dance scenes, jovial rounds of ale drinking, ridiculously large horn choirs at conferences, etc. Most of the music presented in this collection was written by the renowned hornist and teacher Josef Schantl, with some other works by Siegmund Weill, Karl Stiegler, and Anton Wunderer. The name Siegmund Weill may not be remembered by many, but the names Stiegler and Wunderer will be recognizable to those familiar with the lineage of accomplished horn players in Vienna. Stiegler was appointed first horn to the Vienna Court Opera by the estimable Gustav Mahler. He also served as first horn in the Vienna Philharmonic for many years. Wunderer was a member of Schantl’s horn quartet and a prolific composer of horn quartets.

The order of the musical selections on this historical collection presents a delightful, imaginary journey. We hear on the first disc a musical journey through the periods of the hunters’ day, from a morning greeting, to the hunt itself, the death of the quarry, and even the horn calls for each beast. The journey continues with pieces representing various hunting regions, an homage to St. Hubert, some dancing music, and a trip to the tavern. The second disc is comprised of forty-eight fanfares composed in honor of princes, dukes, and various other aristocratic figures of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and its allies, each introduced by a “master of ceremonies” who announces the title of the dedicatee.

The second set of CDs is an interesting collection of contemporary pieces for hunting horns. All compositions on the set are by Hansjörg Angerer and Paul Angerer (both gentlemen have the same surname, but there is no relation). The styles of the contemporary pieces range from solemn hymns to raucous fanfares. At times the music is reminiscent of traditional hunting calls and fanfares, at other times it is reverent, devotional (think Rheingold or St. Hubert Mass), and in other moments, these contemporary pieces can be strident or even playful. Interestingly, there were times during my listening that I was reminded of bluesy and jazzy harmonies and melodies (I could swear there was a brief quote from “Hello Ma Baby” in one of the pieces).

Hunting enthusiasts will be pleased to know that both of these CDs were produced with financial help from the International Council for Game and Wildlife Conservation (www.cic-wildlife.org), an organization devoted to preserving wild animals for sustainable hunting. CIC works on many conservation fronts, including the promotion of “cultural inheritance.” These two excellent CD sets certainly fit that mission since they record both historical and contemporary works for the hunting horn.

The sound quality on both recordings is top notch and it must be stressed again that the playing is incredible. My one gripe about the recordings is an unfortunate error with the breaks between tracks on the collection of contemporary music. There are a couple of moments where I heard the sound of the horn players breathing, as if in preparation to play, but this occurred at the tail end of a track and not at the beginning of a new track. It was a little unsettling to hear a preparatory breath and be given the feeling of anticipation, only to be forced to wait through the break in tracks before hearing the opening notes of the next piece.

--Eric Brummitt

[Editor's note: at the time of publication the website link for the CD publisher was not working, so certain details such as cost and year of publication were unavailable.]