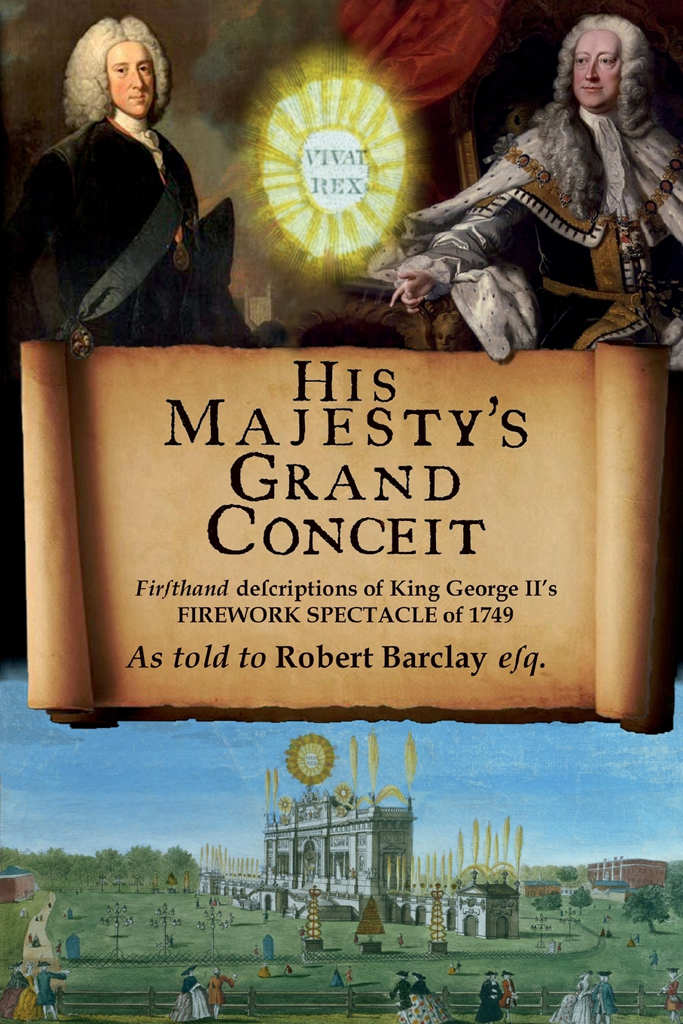

His Majesty’s Grand Conceit. By Robert Barclay (Loose Cannon Press, 2020). 294 pages. ISBN 9781988657196. www.loosecannonpress.com (Available in-print or as an ebook through Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

His Majesty’s Grand Conceit. By Robert Barclay (Loose Cannon Press, 2020). 294 pages. ISBN 9781988657196. www.loosecannonpress.com (Available in-print or as an ebook through Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

George Frederic Handel’s Music for the Royal Fireworks (HWV 351), composed in 1749, is certainly one of the most beloved and splendid pieces in the early brass repertoire. The work was commissioned by King George II of Great Britain to celebrate the end of the War of the Austrian Succession and the signing of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748. This, Robert Barclay’s fifth work of fiction, is a historical novel where the author puts much meat on the bones of a possible scenario of the preparation and the grand event of April 27, 1749 where an estimated audience of 12,000 people jammed into London’s Green Park to witness a spectacular fireworks display and hear Handel’s music.

As we come to expect from the author of the definitive study of Nuremburg trumpet makers, Barclay does his historical homework. The cast of characters of the story are all real figures who actually participated in the event of 1749. The celebration was the brainchild of King George and was clearly inspired by his inflated Royal Ego—he wanted the biggest, best, and most opulent fireworks display ever presented. The music was a second thought, but perhaps the tale surrounding Handel’s involvement and discussion of his work will be most interesting to HBS members. Where Barclay is most clever is his imaginary plot of how the event came to pass. His description of this theatrical production includes constant bickering among the main players, particularly the squabbles among the French, Italian, and English and well as the backbiting and jealousy between members of the various official bureaucracies. The structure of the book is a presentation of the thoughts of the various characters laid out in diary form. The main responsibility for the event is given to John, 2nd Duke of Montagu. He in turn delegates many chores to Charles Frederick, the Surveyor-General of His Majesty’s Ordinance, and much of the labor is then foisted on various workers and other officials. They do their best to undercut their associates, cover their own royal asses and, of course, kowtow to King George. A subplot concerns how Montagu and others work in schemes to feather their own financial nests. The leading experts in fireworks displays and architectural theatre design were foreigners, Gaetano Ruggieri and Giovanni Servandoni, and the nationalistic tension between them and their English counterparts is hilarious. It’s ironic in that the event is a commemoration of a peace treaty.

King George is initially opposed to having music performed at the fireworks display. He objects particularly to having strings. Montagu cleverly convinces the King to include music, and through much arm-twisting, Handel is engaged. The result is a five-movement suite in D major for wind band scored for twenty-four oboes, twelve bassoons, contrabassoon, nine trumpets, nine horns, three pairs of kettledrums and side drums. The imagined exchange between Handel and Montagu is very clever—particularly Handel’s supposed low view of trumpeters and wind band music in general. The King demands at least twelve trumpets and twelve horns. Handel can’t abide by the command and won’t score more than nine each. When Montagu tells the great composer that his Royal Highness has affection for serpents and wants them included in the piece, Handel becomes apoplectic.

Little has come down to us concerning the music. Barclay conjectures that Handel, who was concerned about his reputation being sullied by his involvement with this “low” sort of music, has Montagu use his influence to keep the music reviewers away. While Handel’s great music is a staple of the modern repertoire in both the original band instrumentation and his re-orchestration to include strings, the actual fireworks display was somewhat of a catastrophe. Part of the giant structure from which the fireworks were shot, dubbed the “machine,” caught on fire. A soldier was killed in an explosion, stray bombardments went flying, and a woman’s dress was caught on fire before a sudden downpour put an end to the event. Can you imagine, rain in London?! In keeping with the drawing of King George’s royal personality, Barclay chose to have the King either ignore or not notice the disastrous activities going on. He wanted the best and most splendid fireworks display ever presented. By George, he was going to have it, reality or not!

Bob Barclay gives us a completely enjoyable imaginary tale of the Royal Conceit of 1749—a plausible scenario, which, in many ways, adds a vivid element to our understanding of this historical event.

-- Jeffrey Nussbaum